Sluzki in 1979 developed a model for understanding immigrants before and after migration. According to Sluzki, the continuum of the process of migration can be broken down into discrete steps. Similarly, despite the culture and the circumstances of each family, “The process of migration, both across cultures and across regions within cultures, presents outstanding regularities” (p. 380). He differentiated five stages in the process: preparatory stage, act of migration, period of overcompensation, period of compensation, and transgenerational phenomena.

Gonzalves (1992), using primarily Latin American refugees, summarized the Grove and Torbion model as a theoretical basis for understanding the psychological stages through which refugees pass as they establish links to the new culture. He provided a practical application of the three psychological constructs that Grove and Torbion applied to individuals functioning successfully in their homeland. Both Gonzalves and Grove and Torbion postulate the existence of four resettlement stages that may be applied to understand the experiences of refugee families. These two models relied solely upon the authors’ experience working with immigrant and refugee families.

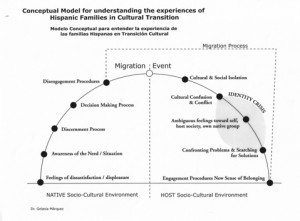

Using both the qualitative data derived from the 35 interviews done on Marquez (2000)’s study and some descriptions and features of the transitional models mentioned before, the researcher designed a model where each of the migratory-acculturative processes described by the families interviewed has its own space. The placement of the parents along the continuum after migration was not based on their length of time in the United States but on the full appraisal done by the researcher of the feelings and attitudes reflected by the parents during the process of interviewing.

In an attempt to represent graphically the continuum between both processes using a 180-degree semicircle curve, it is divided into two major halves to encompass (a) the stages developed in the native sociocultural environment, and (b) stags developed in the host sociocultural environment (Figure 1)

Preparatory Stage (Sluzki) or Period Before the Migration Event

1. Awareness of the situation: Parents perceived the opportunity to better themselves and to provide better educational opportunities for their children as the primary purpose for coming to the United States. Other parents became overwhelmed by political events beyond their control because of threats to their lives, disappearances, or the outbreak of war. Family reunification, better own education, and medical reason

were also reasons stated by the sample studied (all cases but 11b).

2. Discernment process: Only 6 of the 16 cases who are currently married migrated together to the United Stats. For these six cases the process of discernment involved contemplating the possibility of dismembering the family, either because one member of the couple migrated alone or because the couple left their children behind (Cases 12 and 20).

In the four cases (1, 7, 9, 3) where the husband came first and later helped his wife and children to migrate, the discernment process was precipitated by the presence of other family members in the United States (who also migrated alone, leaving their nuclear family behind), and by the need to test the risks involved in the process of entering illegally into the United States. Parents’ responses present the step of discernment as a very brief stage in their movement from one country to the other. Usually the mothers elaborate more than the fathers on it.

3. Decision making: This step involves concrete moves by family members toward a commitment to migrate; for example, visiting and applying for a visa at the consulates of the United States in their countries or with the contactos to find a safe way to migrate through the border. Seven of the 35 parents stated that the decision was a joint family decision, but six parents (one husband and five wives) stated that the decision was made by their spouses. These six parents stated their discomfort with this fact and acknowledged how that situation had affected the harmony of their family life later. One parent came in his adolescent years with his mother.

4. Disengagement procedures: All families interviewed said that they anticipated periods of loneliness and rootlessness, but none of them foresaw the move to the United States as a period of crisis that would encompass changes, modifications of their lifestyle, and even going through processes of renegotiation of their own personal identity and of their family internal organization. All families stated that they never anticipated staying in the United States for more than a “few years.”

Act/Event of Migration

Although the very fact of migration constituted a brief transition from one airport to another for 22 parents of the sample, for 13 other parents the act proper took a considerable time, risks, and emotional as well as economic effort. Those parents who migrated legally always had access to institutions in the country of adoption, whereas the others who migrated illegally experienced mistrust and alienation from mainstream institutions until their situation became level. The majority of these immigrant families managed to establish and maintain a relative moratorium on the process of acculturation and accommodation for months.

Period After the Migration Event

1. Cultural and social isolation (called by Gonzalves, 1992, early arrival) (1w, 3h, 3w, 8h, 19w). Parents began to feel the stressful nature that the move carried. The difference in language, education, and life style accentuates the difficulties and may lead to isolation from the mainstream society. As happened with 8w (3 years in the United Stats), she and her family became progressively enmeshed within their own extended family network and their ethnic group network.

Parent 3h has experienced difficulty in adapting the old family functioning rules and he was also unable to adopt or develop new family rules conducive to effective functioning in the new country; thus he has increased emotional restrictions around his wife and daughters and is imposing the traditional values in a rigid manner.

Parent 19w migrated alone with no relatives in the United States; the loss of an extended family support precipitated her feeling of incompetence and doubt about individual and collective abilities to cope effectively with the new culture. On the other hand, 8h migrated alone to meet here with his wife, child, and his wife’s extended family. Although he expressed feelings and difficulties similar to those of the other four parents, he appears to be less stressed and fearful than they are.

2. Cultural confusion and conflict (called destabilization by Gonzalves, 1992, and period of decompensation or crisis by Sluzki, 1979) (1h, 5h, 5w, 6h, 9h, 9w, 14h, 15h). This stage is characterized by upset and crisis, usually associated with a sense of rootlessness (Sluzki, 1979) and the inability of the family to mourn the loss of the old country (4h, 5w, 9h, 9w). According to Gonzalves (1992), the cognitive and behavioral destabilization are crucial in making possible the intercultural learning in order to make sense out of the new culture. The parents’ expressions regarding changes against mainstream culture (1h, 9h) or toward mainstream culture (6h, 15h) are good examples of the confusion and conflict (9w, 14h).

Variations in the adaptation rates tend to be more evident between members of the couple that migrated at different moments (Case 6), between parent/child(ren) (Case 1), and between the grandparent/grandchild(ren) (17w). Three of the wives stated this difference threatened the marriage stability of three cases ending in divorce (2w, 13w, 16w).

Grandparents of Cases 7, 8, and 16 not only found themselves under the pressure of being “parental substitutes” while grandchildren clearly fought against being accountable to their “old-fashioned” grandparents, but they felt the burden of having the sole responsibility for the chores at home. In addition, newly arrived members of the extended family, either grandparents or other relatives who are incorporated into the family system while “they are finding their own way in the society, ” interrupt the healing process, adding more stress to the situation (Cases 12 and 16).

On the other hand, as parents begin to receive new cultural information and/or to experience different cultural perspectives, they challenge parents’ accepted values and beliefs formed in the native sociocultural environment. The reaction may be an attempt to get in touch with one’s history, culture, traditions, and to use as a reference group one’s own culture (6h).

3. Ambiguous feelings toward self, the new society, and the group left behind (7w, 10w, 11w, 12h, 12w, 16w, 17h, 17w, 18w). Also as a result of both new cultural information received and new cultural perspectives experienced, immigrant families have to accept the ineffectiveness of a very important linkage of their identities: their already attained capabilities and aptitudes to function in society (17h). Consequently, their self-confidence deteriorated and they need to begin a process of renegotiation of their identities.

Other sources of conflict arise when the family finds discrepancy between what was originally expected and the realities of life in the new country, as well as the acknowledgment by family members of his/her unmet needs with regard to the extent of the advantages derived from migration (12h, 12w, 17h, 17w).

The attachment or loyalty to their native culture may influence the way in which these immigrants perceive their own internal resources, adapt to their new environment, and make plans for the future (7w). For children who are recent immigrants there is a need to adapt to the new culture in order to fulfill family search for a better life and to show their appreciation to their parents (17).

4. Confronting conflicts and searching for solutions (called exploration and restabilization by Gonzalves, 1992) (2w, 8w, 10w, 11h, 11w, 13w, 15w). The major characteristic of this stage is the attempts of immigrants to bring the two cultures together and to tolerate the conflict and anxiety of crossing cultural boundaries. New cultural behaviors will become integrated both into family customs and into the self-concept (valued by the individual). At the same time, remaining linked to one’s own ethnic group is essential for maintaining feelings of continuity with the past and for obtaining information and feedback about new learning strategies (8w, 10w).

5. New sense of belonging (called return to normal life by Gonzalves, 1992) (4h, 4w, 6w, 10h, 20h, 20w). In this stage, individuals experience a sense of self-fulfillment with regard to cultural identity (10h: “I am Mexican American”). Conflicts and discomforts experienced before have been resolved, allowing greater individual control and flexibility. Parents 4h, 4w, and 6w, for example, explained how they selected the particular values of their native culture to retain as part of their self-concepts and how they came to respect and understand the values of their new country. For all of them the positive side of the experience outweighs the disruptive nature of the stress and how they emerge from the process with new individual and collective strengths. However, it is clear that their adjustment has been in dependence on the extent to which the reasons for migration become a reality. In addition, the relative economic stability has freed them to confront the painful feelings and memories that were suppressed in the service of learning to live in a new environment.

Implications

The process of acculturation experienced by immigrant Hispanics has been the topic of interest to a great number of investigators in recent years, especially in the states of California, Florida, and New York, ports of entry for a large number of immigrants. In these states during the last 2 decades there has been a steady influx of Hispanic, Haitian, South Asian, and other ethnoculturally diverse families. It is very probable that the social institutions most affected by these changing demographics are the private and public schools that have received and continue to receive the children of those immigrant families. For these families, the school has had to perform an extraordinarily difficult role, that of serving as “an intersection between the home culture and the mainstream American culture” (Provenzo, 1985, p. iii).

Esquivel (1985) recommends that practitioners serving children whose culture the school psychologist does not know perform a careful evaluation of the child and the family. Consequently, professionals in the educational field should be aware of the consequences that the migratory and the acculturative processes have on these families. This is especially true for those immigrant families from countries that have undergone social and economic outbursts. As the review of literature and this study illustrated, both processes can produce family disorganization and the likelihood of persistent handicaps in its members due to language barriers, lack of knowledge of rules and regulations, limited financial means, and lack of adequate reference groups.

One of the two end products of the present study is a qualitative semistructured bilingual questionnaire. As was mentioned in Chapter III, the content validity of the questions was initially examined by two independent bilingual professionals in the social studies field. The Immigrant Family Acculturative Interview (IFAI) can be used in the future as an instrument not only to assess the acculturative process of immigrant Hispanic families within its own particular context and circumstances, but to tailor the possible responses to help them in their specific circumstances. Future research can also find the psychometric characteristics instrument so it can be used not only for qualitative, but for quantitative, studies.

Based on Marquez’s study (2000) study it appears that the possible responses to immigrant families in cultural transitions may range from a combination of information, education, opportunities for emotional ventilation and support, contact with other families who have similar difficulties, professional availability during times of crisis to the creation of intermediary structures that mediate between the individual family and the new culture.

Education is an important step in regaining the sense of belonging. When a person enters a new or strange society with its own ready-made rules for behavior, new and more appropriate behaviors must be learned to fit into the new group. By encouraging a family educative environment the confusing ambiguity of its members is probed rather than avoided, and both parents and children not only maintain a sense of self-meaning and worth but also learn to cope step by step with the challenges of the new and different environment. Finally, the provision of factual information helps the different generations gain an understanding of what is expected within each other’s worlds, and the rules and norms by which each group behaves.

As this study found, intermediate structures like schools and churches are very important in the first years after migration. The review of the literature stated that the interaction with those social structures are dropped as the family is less in need of structural support and is more able to profit from direct exposure to the new environment. However, the continual interaction that immigrant families have with both environments within those structures, and the short- and long-term consequences of such interactions pose a challenge to research the nature of these dialectic and transactional influences.

The second end product of the present study is a comprehensive model applicable to immigrant Hispanic families in cultural transition and interacting with a multiethnic society. The purpose for developing this model is to provide the opportunity to study the different stages that precede and follow migration and, based on parents’ responses, to describe some of the features that appear to be related to each one of those stages. Future studies could address the aforementioned model, its stages, and characteristics and factors that intervene in favor or against the acculturative process of the ethnic families. Consequently, the current study is a step forward in providing a framework that can be tested by both qualitative and quantitative studies, but it can also guide the development of more effective interventions for immigrant Hispanic families in cultural transition.

This study has contributed to illustrate a new perspective on the process of acculturation when it describes how the interaction between Hispanic parents and both sociocultural environments, the host and the native, have influenced their process of adjustment after migration. Second, the sample presented the viewpoints of immigrant parents from eight Latin American countries. The specific length of time in the United States selected for the sample of this study (from 2.8 years to 25 years) provides comprehensive information about what happens during the first years after migration. The sample also had a significant number of parents (13 out of 35) who entered the United States illegally and who are currently, at least, legal residents with stable jobs–some of them are owners of their own small businesses–and who presented themselves as responsible members in the community where they currently live.

As was stated before, qualitative research offers no opportunity for replication as is possible with quantitative research. However, the data obtained from this study will remain as a rich source of evidence that can be used again, even as part of another study. The close-up description of immigrant Hispanic parents in their real-life context can be useful as a framework for generating and testing hypotheses. In addition, the review of the findings presented in Chapter IV offers a full range of opportunities and perspectives to uncover new meanings and relationships to both processes, migration and acculturation.

The researcher agrees with Vega (1990) who recommended systematic ethnographic studies regarding language and the role it plays in preserving family practices and ethnic identity. Similarly, complementary studies using a common theoretical framework would show how the historic and economic circumstances of different ethnic Hispanic groups determine the characteristics of their migration and, furthermore, influence their disposition to follow through the process of acculturation. Finally, further research is needed on the construct and theories of the process of acculturation of immigrants when the host American reality is no longer monocultural but multicultural. Similarly, this study postulates that the influence that the so-called Hispanic culture has as a major contributor to the cultural life of the community is an important factor to be considered in further research on the acculturation of Hispanics in certain areas of the United States.

Finally, the results of Marquez’s study (2000) offer preliminary support to the utility of qualitative research in studying processes that occur over a period of time and where more than one factor has an influence on it.

(This model as well as its implications are the conclusion of the 2000’s Doctoral Dissertion of Gelasia Marquez, Ph.D, )